L’Horreur

An examination and celebration of the French New Wave of Horror

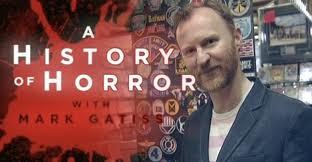

In case it needs saying, horror films are not a uniquely English-language phenomenon (and for a historic perspective, Mark Gatiss’ excellent, Horror Europa series is a worthwhile watch).

At the moment, for me, the nations punching above their weight in terms of horror fare would include Britain (note, not just England; in recent years alone, we have seen Ireland’s excellent The Inside, Scotland’s Outcast, and Wales’ Splintered), Japan, and those inventors-of-cinema themselves, the French.

Since its inception in the early twenty-first century, the French New Wave(growing out of the broader French New Extremity movement) has provided some of the best, most imaginative and ground-breaking horror ever made. Whilst ostensibly paying tribute to existing horror sub-genres like slasher,revenge films, home invasion, and particularly body horror, and showing clear influences from classic directors like Cronenberg and Hooper, New Wave has gone wildly off in its own direction, and produced some extra-ordinarily original and challenging stories. It’s also provided some of the strongest female leads in recent cinema; and they need to be strong because boy, do they suffer!

Needless to say, in touring my personal favourites, spoilers will be included….

2003 gave us Haute Tension (High Tension for the US market, Switchblade Romance for the UK market), which tricks us into thinking we’re watching a classic slasher flick (albeit a very well-made one), but we’re not. Well we sort of are. I’ll explain: we begin by following female besties Alex and Marie on a journey into the idyllic rural French countryside to stay with the former’s parents.

It’s all very nice and pleasant – so that’s obviously not going to last – and indeed when a stranger comes knocking at the door in the middle of the night, we head into fairly classic home invasion / slasher territory, with the hidden-faced killer being exceptionally gory and violent in his murderin’.

Marie manages to hide initially but when Le Killer drags her friend Alex off to his van, she goes off in pursuit of them. We think we know what film we’re watching from there on in, as the violence and gore escalates, but we don’t, as is nicely revealed in the film’s denouement.

There is no killer: it’s been Marie all along; mad, bad, psychopathic, delusional Marie, and she did it all because she’s secretly infatuated with her friend, Alex.

The things young people do for love.

Haute Tension made Time Magazine‘s ten most ridiculously violent films list so that in itself is a commendation.

In 2006, the succinctly-named Ils (Them) was released. Mon Dieu, this is tense, tense tense!

A mother-and-daughter are murdered after their car breaks down in rural Romania: the perpetrators are unseen, but when we cut to Clementine and her boyfriend Lucas (recently emigrated from France) you can’t help feeling the two parties are going to get acquainted in the worst possible way…..

And so it goes: our young French couple are awoken from a cosy night in by the sounds of their car being broken into.

Then off we go into some highly-taut home-invasion, chase-through-the-woods and stumble-through-the-sewers stuff, pursued by an unknown pack of savage opponents.

What’s interesting here, though, is that the film chooses feral youths as its antagonists (in common with later British horrors, F and Eden Lake). These homicidal hoodies, it emerges, are motivated not by greed nor revenge, but by a kind of sociopathic boredom.

When both Clementine and Lucas have been brutally dispatched (you’d guessed that was going to happen, right?), we follow the residual group who emerge from the woodland and hop on the bus home.

When later interrogated regarding the murders, the youngest of the children (they were aged ten to fifteen, so we’re told) simply comments that they (Clementine and Lucas), ‘wouldn’t play with us.’

Kids today, huh?

A year later we got Frontieres (Frontiers), again, like Haute Tension, fromEuropaCorp (thanks, Jean-Luc Besson!)

Starting off with the election of a far-right politician to the French presidency (cleverly mirroring the nature of the film’s eventual antagonists), we follow a bunch of compadres – Alex, Tom, Farid, Sami, and the pregnant Yasmine – hoping to pull off a robbery under cover of the riots that have kicked off in protest against the new President.

Predictably, all does not go well.

When Sami gets shot, Alex and Yasmine take him to hospital while Tom and Farid head off with their ill-gotten gains to a family-run inn on the border, to wait for them.

Innkeepers Gilberte and Klaudia seem like friendly types, but when they declare that the room is free and even get a bit flirty with the two men, you just know things are going downhill.

It emerges that Gilberte and Klaudia are part of a large and distinctly homicidal extended family (we also meet Goetz, Hans, Karl, and patriarch Von Eisler)and as events turn spectacularly bloody, we might initially have thought these were French cousins of Leatherface and family (from the Texas Chainsaw Massacre).

But no, Von Eisler is a former, and practising, Nazi, and when Yasmine (and Alex) turn up, it looks like she will get the chance to join the French Family Fascist, as breeding stock, natch.

Lucky girl.

The guys get butchered in a variety of unpleasant ways (top marks probably going to Farid who ends up getting cooked alive in a boiler), leaving just Yasmine (with newly-recruited ally Eva, one of the children the family keep in the mine below the inn) to fight back.

And fight back she does, in epic fashion, using knives, axes, and even a table saw in her struggle for survival, before finally getting away and stumbling across a police blockade, the only survivor of the incident.

Did I mention this was one for the gore-lovers only?

And finally, I’ve saved the best for last – for me, the defining masterpiece of French New Wave is 2008’s Martyrs. Threads of the other films run through it, but it transcends them, becoming something truly unique: simply, there is no other film like Martyrs.

It’s powerfully shocking right from the start with a little girl, Lucie, escaping from a life of torture – there is no back-story to her situation and this approach of showing-without-explaining continues throughout the film. We have a few tasters of the next fifteen years of her life, as the deeply-damaged Lucie forms a deep friendship with another girl, Anna.

But director Pascal Laugier decides we’ve been having it way too easy and the next thing we get is Lucie and Anna breaking into a (seemingly) ordinary family’s home and massacring everyone.

Around now, we become aware that something is pursuing Lucie – a horribly-scarred female figure intent on brutalising her – and it catches up with her in the massacre-house; chasing, then attacking her.

Except there is no pursuer – we see from Anna’s point of view that Lucie is injuring herself and that the pursuer is a manifestation of the guilt she feels for leaving another girl behind, when she escaped from her torturers as a little girl.

When she realises this, and that there can never be any peace for her, Lucie slits her own throat and dies in Anna’s arms.

That’s about twenty minutes in, and what’s interesting is that that would usually have been the full film; nice little revenge tale (albeit we still don’t know revenge for what!), a twist in that the monster doesn’t really exist and a tragic end for one of our heroines.

Martyrs is barely getting started though, and is about to take us off in a whole new direction.

Cleaning up the house the day after Lucie’s death, Anna uncovers a secret basement complex and a hideously-scarred, disfigured woman imprisoned there. As she tries to help her escape, a group of strangers turns up and kills the woman. The group’s leader (never identified as anything more than Mademoiselle) calmly explains that she is part a secret society attempting to discover the secrets of the afterlife through the creation of martyrs.

Specifically, they expose their test subjects to extreme, systematic pain in the belief that this will eventually create a transcendental state, with insights into the world beyond this one (for me, this theme of enlightenment-through-pain is very reminiscent of Hellraiser).

Guess who their next subject is?

Again, this is an odd decision narratively, in that Martyrs has given us its final ‘twist‘ about halfway through. What, then, is it keeping in reserve?

What follows is a disturbing montage of Anna’s suffering, in which she goes through a series of reactions, from fear to defiance to rage to frustration. Eventually, the awfulness of her situation overwhelms her and in a hallucinated conversation with Lucie she resolves to ‘let it go’, to abandon hope and identity.

Is this the beginning of the transition into the transcendental state that her captors desire to see?

Mademoiselle certainly thinks so, and delighted with Anna’s ‘progress’, she orders her flayed alive, a procedure that leads her to enter a state described as euphoric.

Hurrying to hear her revelations, Mademoiselle bends down next to the flayed Anna and the receives some whispered words from her.

The secrets of the afterlife?

We never get to find out because whatever she is told is so profoundly terrible that in the very next scene, at the point she was supposed to reveal all to her organisation, Mademoiselle instead chooses to blow her brains out.

If there is a thread of bleakness and a fascination with body horror flowing through all the French New Wave – and there is, for me – then Martyrs takes those aspects to the most extreme places imaginable.

It’s sometimes been grouped – inaccurately in my opinion – with torture porn flicks(such as Eli Roth’s Hostel films) but tellingly, Laugier has pointed out that Martyrs is not about torture nor suffering, but pain.

Nobody does horror quite like the French New Wave – vive la difference!

French flag by Gabriel Oliveira

Article originally published at https://www.tumblr.com/blog/earthworksmovie